PURITY OF POLLS

Dr K K Paul | This article was first published in The Statesman on Thursday, 25 February 2020.

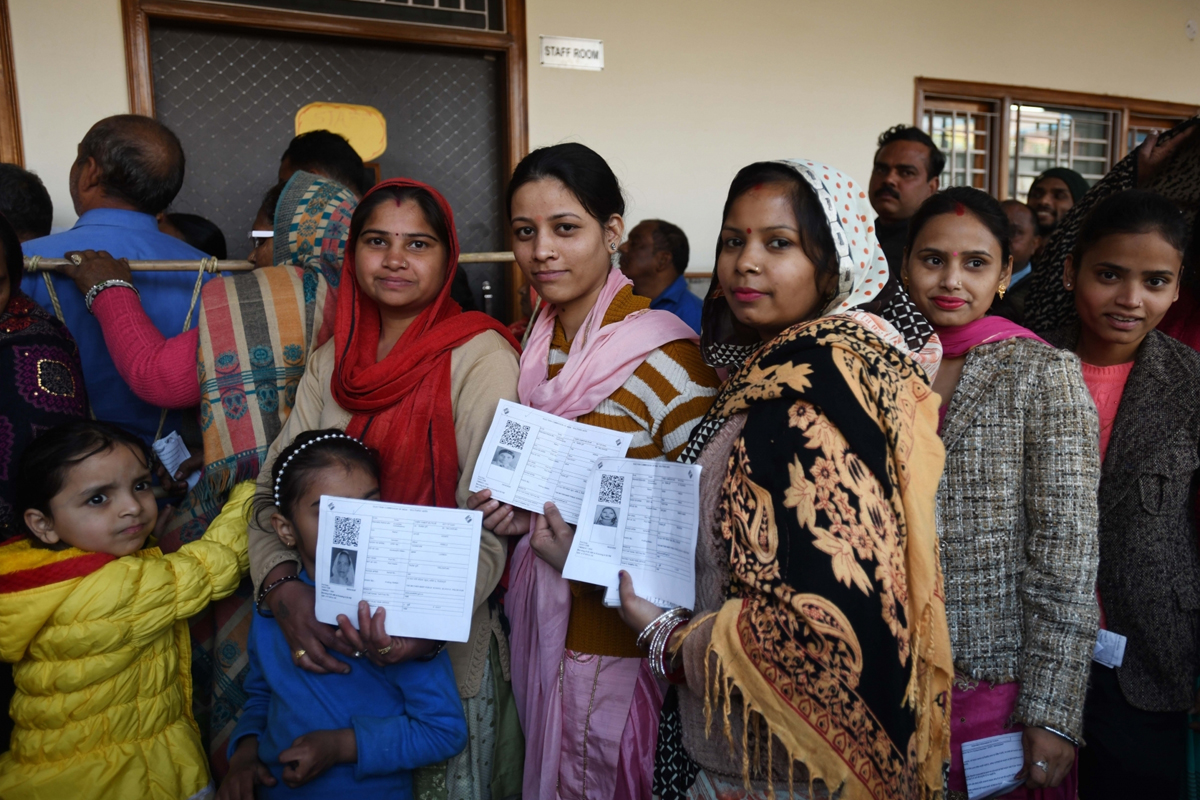

Holding peaceful elections on a gigantic scale for an electorate which is much bigger than USA, Indonesia, Europe, Brazil and Australia all taken together, the Election Commission has played a stellar role in strengthening our democracy. In doing so it has set an example for other countries. With the level of awareness amongst our electorate improving, the entire process has now become more complex and challenging. This also highlights certain important issues which can no longer be ignored and have to be addressed.

Conduct of free and fair elections with transparency and a level playing field for all are integral to any democracy. This is also recognised by our constitution as a part of its basic structure. In this context, the Hon’ Supreme Court has observed “In order to ensure the purity of the election process it was thought by our Constitution makers that the responsibility to hold free and fair elections in the country should be entrusted to an independent body which would be insulated from political and/or executive interference.” The autonomy and independence of the Election Commission, thus, remains an essential prerequisite for the conduct of free and fair elections.

At present, in addition to the Representation of People’s Act, there are certain provisions in the Conduct of Election Rules 1961 and Indian Penal Code, which lay down the general parameters, within which the system has to operate. Besides these, the Election Commission has prescribed a Model Code of Conduct which is applicable to all the stakeholders, political parties, candidates as well as officials and the government machinery, on their role in the conduct of elections. It is the essential rulebook which has to be adhered to in letter and spirit. Its violations can draw the ire of not only the Election Commission, but may also invite judicial intervention. While this Model Code of Conduct had evolved over the years, its real impact was felt for the first time during the tenure of Sh. T.N. Seshan as the CEC. But it appears that the electronic media, in general terms, still remains beyond the Model Code of Conduct.

Over the years, the style of electioneering has undergone a complete transformation and these days in every campaign, media plays an important role. It enables the people to make a well informed choice. In this context, currently, the electronic media, both television and social, on account of their phenomenal reach have virtually occupied the centre stage and have become a major influencing factor in every election campaign.

When the concept of Model Code of Conduct was evolving in the ‘ 60s, only the print media alongwith the radio had dominated the scene. As such, it was left to the Press Council of India, who issued detailed guidelines in 1996 on election related reporting. During the last few decades, advancements in information technology have virtually revolutionised the channels for dissemination of information and in reaching out to people. In this context, apart from the television channels, guidelines in respect of use of social media during election campaign have also been issued by the ECI. Separately, on the lines of the Press Council, The National Broadcasters Association, which is a voluntary organisation, has also issued guidelines for private TV channels in 2011, for election related broadcasts. During a campaign the monitoring is expected to be undertaken by the News Broadcasting Standards Authority.

Amongst the important guidelines are “News broadcasters must not broadcast any form of ‘hate speech’ or other obnoxious content that may lead to incitement of violence or promote public unrest or disorder as election campaigning based on communal and caste factors is prohibited under Election Rules. News broadcasters should strictly avoid reports which tend to promote feelings or enmity or hatred among people, on the ground of religion, race, caste, community, region or language”. Further, the Election Commission of India is required to monitor the broadcasts from the time elections are announced until the conclusion and violations are to be reported to the News Broadcasting Standards Authority for action under their regulations. Thus the NBSA does not take cognizance of the violation, if any, unless reported by the ECI.

This can be seen as a serious handicap in the working of the NBSA, for in certain cases the ECI may not ask it to act, as happened recently during the course of the polls in Delhi. Even without going into the ownership or the shareholding pattern of the channels, their limitations thus stand exposed leaving them vulnerable.

An equally serious problem which remains unresolved so far exists during the campaign for multi phase polling. In such cases, it often happens that the 48 hour embargo may have commenced in one constituency, while full scale campaign continues in other areas scheduled to go to polls later. With the channels enjoy unlimited reach, the 48 hour embargo appears to be observed more in breach. In this context, the Election Commission in its Model Code of Conduct (2019) has stated that “in the era of wide reach of electronic media in the country, it is impossible to block any matter being covered on electronic media in a specific area, state or constituency.” Elaborating further, it has been held by the NBSA that “The media would be entitled to broadcast in regard to a contesting candidate of a particular party in one state, irrespective of the fact that transmission would be seen in other states. Covering a general event relating to a political party which is relevant and of common interest across the country or across a state, which does not extol the public to support any candidate or which does not criticize any candidate in the constituency going to polls, is not a violation of any guidelines.” In other words, both the Election Commission as well as the NBSA appear to have given up on the main issue which in many cases would mean an erosion of fair play and level playing field. This existing practice needs a focussed attention by a group of experts so as to ensure that monopolising the media does not give an unfair advantage to any candidate.

As the ECI deploys special observers to monitor the expenditure incurred by a candidate during the campaign, the monetary aspect has come under a sharper focus. A candidate may spend between Rs. 50 to 70 lakhs for a Lok Sabha seat, depending on the state. Similarly limits on expenditure have been prescribed for a state assembly. On the other hand, the expenditure on the part of the political party for the campaign has no limits. In addition, the source of funding for the political party, whether through bonds or otherwise, is also not known. In the circumstances monitoring a candidate, howsoever close it may be and leaving the larger issue unchecked, appears to be only a half baked exercise with several loopholes. It is obvious that the benefit of this very substantial share of expenditure incurred by the party, accrues in favour of their candidate leaving a serious imbalance in the playing field. It is now understood that the ECI has recommended to the government that the expenditure of the political party for a candidate should be limited to not more than 50 percent or half of the candidate’s expenditure limit.

Both money and media, play a very important role during any election campaign. The existing loopholes in these vital areas need to be plugged for a better and more stringent regulation, only then could we have a level playing field for the elections.

(The author is a former Governor and a Sr. Advisor at the Pranab Mukherjee Foundation)